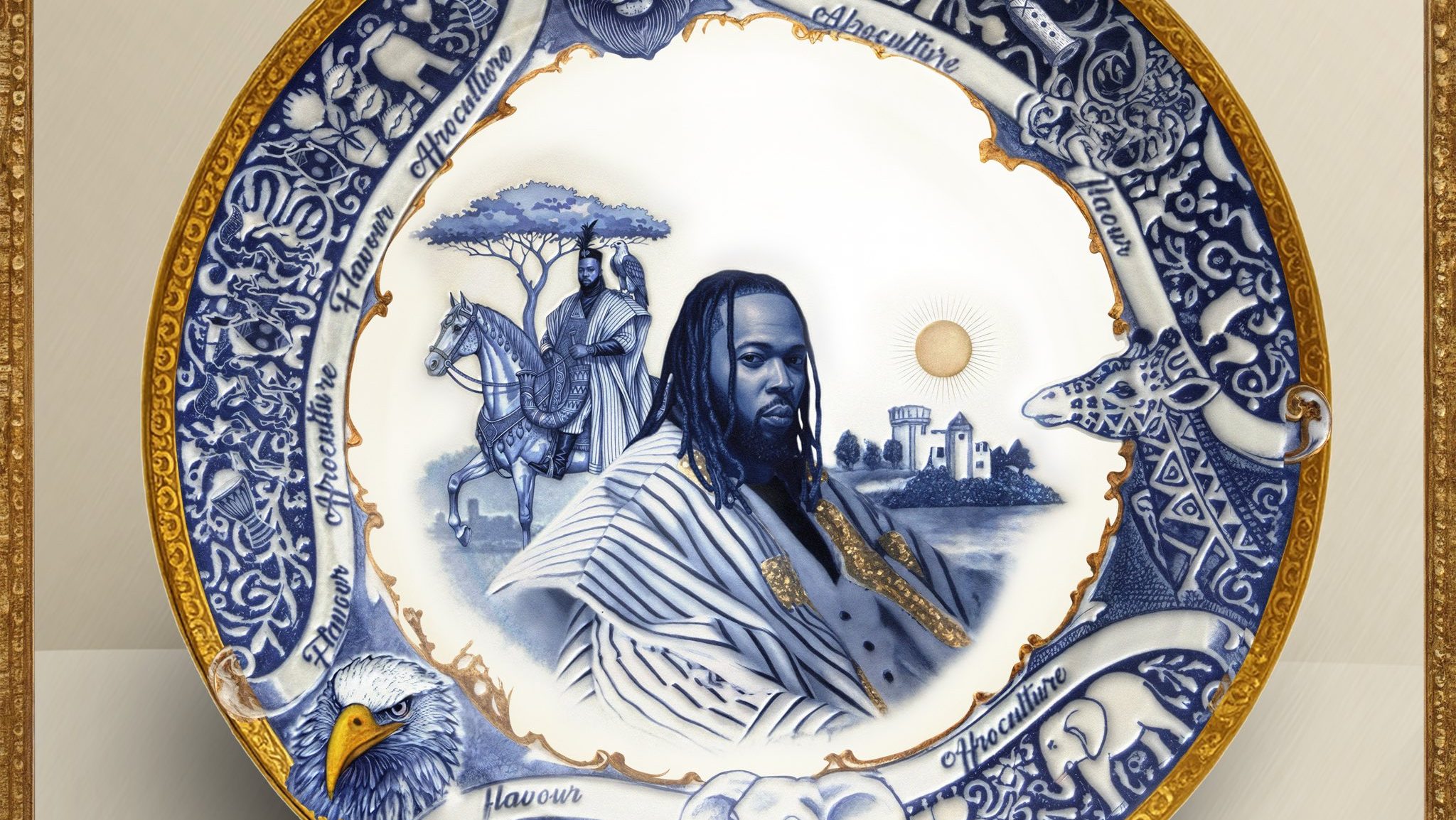

On November 24, TG Omori posted on Twitter. The acclaimed video director who helped define the visual language of modern Afrobeats announced his first album cover: artwork for Flavour’s album, “AFRO-CULTURE.” It should have been a celebratory moment. Instead, the replies filled with a familiar refrain: “This looks AI-generated.”

It’s a scene playing out repeatedly across Nigerian music Twitter. The artist behind the cover for Mavo and CKay’s “Body” posted her initial sketches alongside the finished product, the kind of process documentation that used to settle questions about creative work. The accusations came anyway. The sketches could be fake. The work could be touched up with AI. The artist could be lying.

Nobody knows for certain. That’s the point.

Over the past month, we watched a song with AI-generated vocals of the singer Fave gain traction on TikTok. It was a little dystopian watching something that sounded like her, felt like her, compete with her actual work for attention. The AI didn’t need her lived experience, her studio time, or her creative decisions. It just needed her voice as data. However, she decided to adopt the ‘if you can’t beat them, join them’ mantra and released a version of the song in collaboration with Urban Chords, the entity responsible for the earlier AI version, in a move she called ‘embracing dual authenticity’.

Urban Chords is a gospel music collective that uses AI to create vocals, usually in a choral style. This was showcased on their album, Choir Refix, where they remade several popular Afrobeats songs, such as Asake’s ‘Lonely at the Top’, Libianca’s ‘People’, and Omah Lay’s ‘I’m a Mess’, as choir versions that feel like worship. The album made it to #43 on the Official Top 100, according to TurnTable. As at the time of writing, the album has been taken off Spotify.

The pattern extends far beyond Nigeria. In 2024, an AI-generated track called “Verknallt in einen Talahon” charted in Germany. A fake 1960s band called The Velvet Sundown topped Spotify’s Daily Viral 50 in three countries, accumulating over a million monthly listeners for music that never existed until an algorithm made it. Breaking Rust, an AI artist, hit number one on Billboard’s Country Digital Song Sales chart with over 3.5 million Spotify streams. A new artist, Xania Monet, was signed to Hallwood Media in a multimillion-dollar deal this year. The twist is, “Xania Monet” is actually the work of a Mississippi songwriter who writes the songs and uses the AI platform Suno to create the music.

A recent study published by Deezer found that 97% of people can’t tell the difference between real and AI-generated music. That’s not ‘most people’, that’s almost everyone. Spotify has started removing what it calls “spammy tracks,” pulling down an estimated 75 million songs. The platform now requires AI disclosure for some content. Major labels like Universal, Sony, and Warner have sued AI music companies like Udio and Suno. Over 200 artists, including Billie Eilish, Nicki Minaj, and Stevie Wonder, signed an open letter against AI music in April 2024. But the AI music keeps coming. By some estimates, 30% of tracks uploaded to streaming platforms are now AI-generated. The volume alone is overwhelming.

Nigerian artists didn’t build their global presence through industrial music infrastructure. They built it through authenticity, through specific cultural expressions that couldn’t be manufactured anywhere else. CKay’s “Love Nwantiti” wasn’t just catchy, it captured something particular. Burna Boy didn’t become an international star by sounding like everyone else. Tems didn’t break through by being generic.

TG Omori’s videos shaped how Afrobeats looked to the world. His visual language became synonymous with the genre’s aesthetic identity. When someone like him, returning to work after a failed kidney transplant in August 2024 and a successful one this February, expands into new creative territory, the accusation that he used AI for an album cover carries weight beyond one artwork. It suggests that even the most celebrated architects of Nigerian music’s visual identity can’t be trusted anymore.

The accusation might be wrong. Qiva, the artist behind the Mavo/CKay cover, might have drawn every line by hand. Fave’s voice might still be uniquely hers in ways AI can’t replicate. But the uncertainty is now permanent. Once AI can do something, every human who does that same thing becomes a suspect.

Some people think that AI bands will make it harder for real human artists to break through on streaming platforms. If true, this creates another barrier for Nigerian artists already competing globally against established Western music industries. They would not just be competing with other humans anymore; they would now have to compete with machines that can produce content faster, cheaper, and in higher volume.

The person behind Breaking Rust also creates explicit AI songs under another pseudonym, “Defbeatsai.” The economic model isn’t exactly artistry; it can also be viewed as content farming. Create enough tracks, optimise them for algorithms, and a few will break through. The cost of failure is negligible when production costs nothing. Small independent producers and artists will feel this pressure first. The same streaming platforms that helped democratize music distribution are now being flooded with AI-generated content that makes discovery harder, not easier.

On Nigerian music Twitter timelines, a new kind of conversation is happening: not about whether AI will come to Nigerian music, but about what happens now that it’s here. Artists who built their careers on authenticity now have to prove their authenticity constantly. Listeners who valued the human connection in music now can’t always identify when that connection is real. Platforms that promised to democratize music distribution are becoming indistinguishable from content farms.

Maybe this is just growing pains. Maybe new systems will emerge to verify human creativity. Maybe listeners will develop better instincts for distinguishing real from generated. Maybe it won’t matter. Maybe music that moves people is music that moves people, regardless of its source. Or maybe we’re watching something irreplaceable slip away: the assumption that art comes from lived experience, that creativity requires a creator, that the person whose name is on the work is the person who made it.

Nobody’s quite sure anymore what they’re listening to, or who made it, or whether that distinction still matters. And that uncertainty might be the most significant thing AI has brought to Nigerian music, not the technology itself, but the questions it makes impossible to answer.

Leave a Reply